Why is life expectancy so low in Black neighborhoods?

Andre M. Perry, Carl Romer, and Anthony Barr

December 20, 2021

- 8 min read

Follow the authors

Earlier this year, the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) published data showing a 1.5-year decline in national life expectancy in 2020, largely due to the COVID-19 pandemic, which took the lives of approximately 375,000 Americans that year. The NCHS reported that white Americans’ life expectancy declined by 1.2 years; for Black Americans, that number was 2.9 years.

This racial disparity in life expectancy is a lagging indicator of disparities that have existed throughout the pandemic. According to the most recent Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data, Black people are 1.1 times more likely than white people to contract COVID-19; 2.8 times more likely to be hospitalized with the virus; and two times more likely to die from it. These disparities help to explain why, when adjusting for age, Black people account for 22.1% of the nation’s COVID-19 deaths despite only comprising 12.8% of the population.

The causes of these racial disparities are hotly debated, and many fixate on the role of individual behavior—for example, a recent Brookings analysis cited vaccine hesitancy as a key driver of disparate death rates. But while personal behavior matters, social determinants of health at the local level play an outsized role. Because de jure and de facto segregation concentrated Black Americans in specific locales, racial injustices have occurred through place-based discrimination: disproportionate exposure to pollution and hazardous waste, harmful zoning practices, and post-disaster displacement, to name a few. Rather than blaming Black people for their suffering, the conditions of place must be examined to understand the mechanics of racial discrimination that contribute to that suffering.

Two findings highlight hyperlocal variation in life expectancy prior to the pandemic

Finding #1: Neighborhood life expectancy correlates with neighborhood demographics

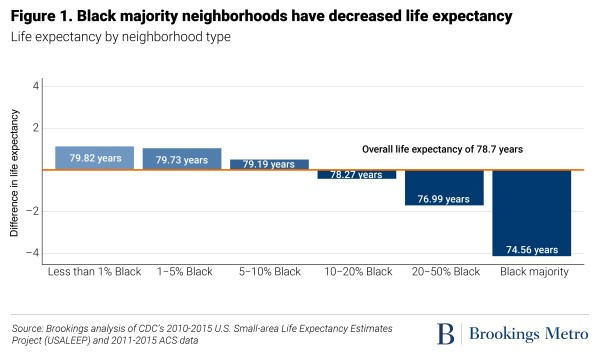

We compared life expectancy across neighborhoods where the population of Black residents ranged from less than 1% to over 50%. The graph below shows that at the national level, neighborhood life expectancy decreases as the Black population percentage increases. Neighborhoods with a 10% Black population or higher have an overall life expectancy lower than the national average of 78.7 years. Black-majority neighborhoods have a lower life expectancy by approximately 4.1 years, and neighborhoods with a Black population of less than 1% have a higher life expectancy by around one year compared to the national average.

Throughout the pandemic, most geographic analyses of differing health outcomes focused on comparing different states, metro areas, and counties. The comparisons are important, but these geographic areas are not homogenous units. There can often be as many stark differences found within a metro area as are found across metro areas—a fact underscored in our second finding below.

Finding #2: Neighborhood life expectancy disparities exist relative to the surrounding metro area

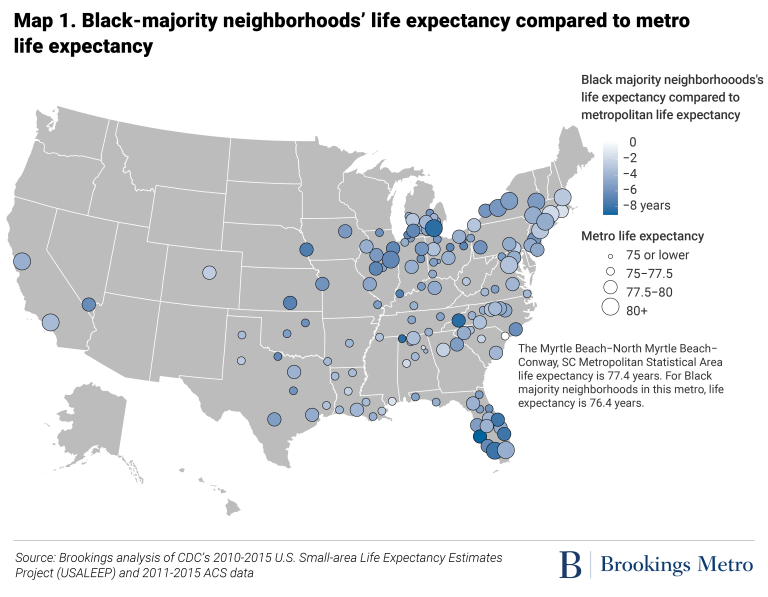

We found that Black-majority neighborhoods had relatively lower life expectancy when compared to the aggregate metro area in which those neighborhoods were located. As shown in the map below, the difference in life expectancy between a Black-majority neighborhood and its surrounding metro area can be as high as nine years.

Both findings illuminate the fact that racial gaps in life expectancy manifest as place-based problems. But one alternative way of interpreting these findings is that Black people might carry life expectancy decline with them into the neighborhoods they live in, such that the crucial variable is the people, not the place. Supporters of this view could point to the fact that there are persistent (though narrowing) nationally aggregated racial gaps in life expectancy that extend backward for many decades.

https://www.brookings.edu/articles/why-is-life-expectancy-so-low-in-black-neighborhoods/

Comments