It's dangerous work that comes with the risk of lead poisoning and little pay. Inamul Hoque, 35, one of the workers – who are mostly from the flood-prone Gaibandha – works for 12 hours a day to salvage a minimum of five tonnes of lead scrap.

"We can hardly fetch Tk8,000-Tk10,000 a month," he said. The remuneration is neither reflective of the risk nor the fact that the bhatti workers – generally debt-fatigued and marginalised 'cheap' labour – are the nuts and bolts behind the supply chain of lead batteries.

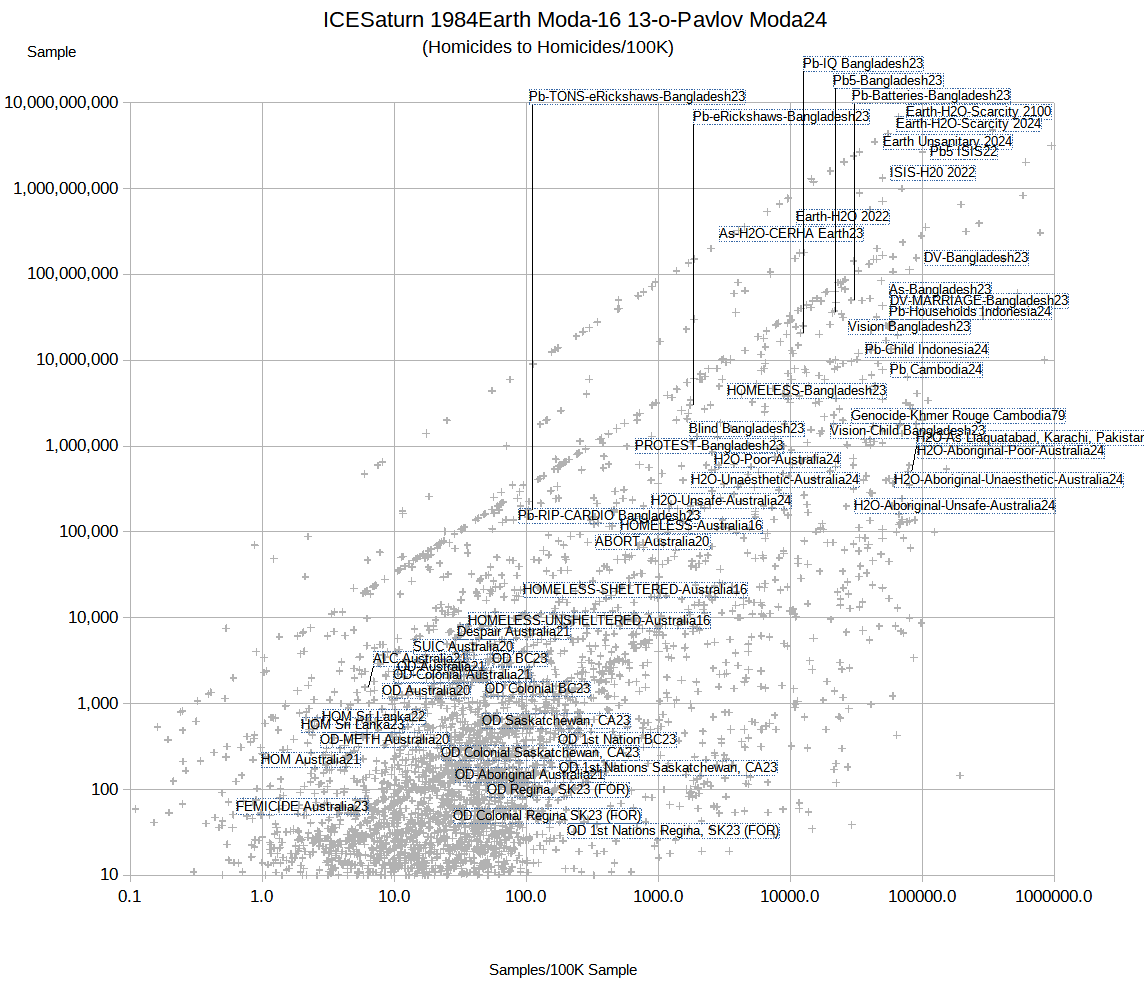

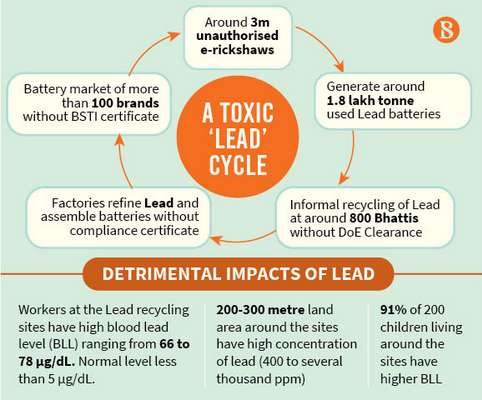

The demand for lead batteries has grown over the years owing to the rise in the use of zero-emission customised e-rickshaws – banned by the government in 2021 on major roads following the High Court directives since 2014 citing them as risky and unregistered.

Not only that, the batteries used are not certified by Bangladesh Standards and Testing Institution (BSTI). And unregulated and unauthorised lead factories pose a plethora of health risks.

But despite all this, there still remain more than 3 million e-rickshaws in Bangladesh currently, according to the Battery-run Easybike and Rickshaw Drivers' Movement Council, which has branches in 50 districts.

It's not, however, all doom and gloom. Lead batteries are a prospective additional Tk500-1,000 crore per annum industry, but without regulations in place, it's only a ticking time bomb.

The source: Tale of the bhattis

Comments