I HAVE witnessed first-hand the devastating impact of environmental hazards on health and society. Yet, a few hazards pose as insidious a threat as lead poisoning, an issue that has lingered in the shadows of public health discourse for far too long despite its devastating consequences. Bangladesh ranks in the fourth position globally in terms of lead exposure, according to a recent World Bank report, and more than a third of our children have blood lead levels far above the safe threshold. This issue is, however, not limited to the vulnerable populations of children and the impoverished. It threatens us all.

Lead poisoning is pervasive, affecting nearly every segment of society. In children, particularly those under five, exposure to lead irreparably harms their development. A 2020 UNICEF and Pure Earth report estimated that about 35.5 million children in Bangladesh are exposed to high levels of lead. The consequences include permanent brain damage, learning disabilities and behavioural issues. For adults, the consequences of lead exposure are no less severe. Exposure has been linked to increased rates of cardiovascular diseases, kidney dysfunction and reduced fertility, among other serious health conditions.

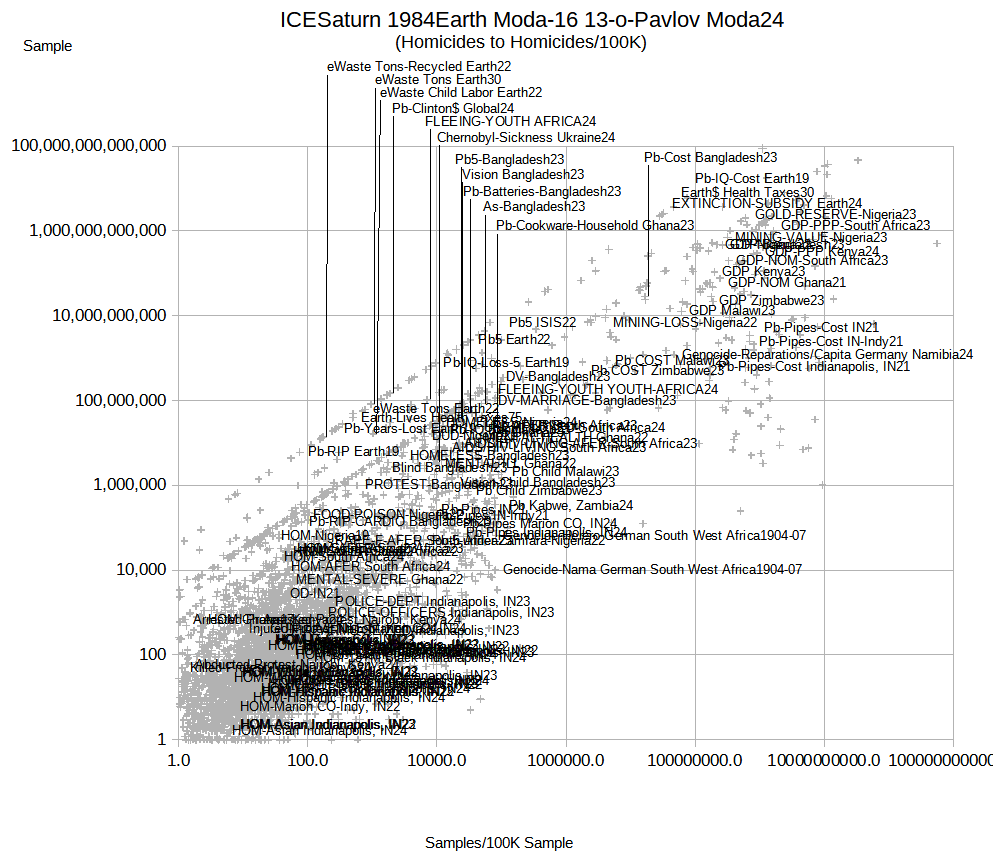

The economic impact of this crisis is equally staggering. According to World Bank estimates, Bangladesh loses a shocking 3.6 per cent of its gross domestic product annually to lead exposure, totalling nearly $10.9 billion a year from cognitive damage alone. Including cardiovascular-related costs in adults, the financial loss skyrockets to more than $28.6 billion. This economic toll, coupled with the human sufferings that lead exposure inflicts, makes it clear that lead poisoning is not merely a health issue. It is a national crisis.

Roots of lead poisoning crisis

LEAD exposure is deeply woven into the fabric of everyday life. The primary sources of contamination stem from informal sectors where awareness and enforcement of health standards are scarce. An informal recycling of lead-acid batteries is, perhaps, the largest source. In Bangladesh, an estimated 50 million batteries are disposed of or recycled every year, largely in unregulated or ‘backyard’ facilities. These operations are often located near residential areas, where workers, many of whom are children and nearby residents, are directly exposed to a high concentration of lead dust.

But the problem extends beyond battery recycling. Lead is present in a myriad of household items: aluminium cookware made of recycled metals, lead-laden paints, contaminated spices, cosmetics and even toys. Turmeric, a spice ubiquitous in cuisine, is often adulterated with lead chromate to enhance its colour, exposing millions to chronic low-level lead exposure with every meal. The pervasive nature of lead in such common items means that exposure is a daily reality for most Bangladeshis, regardless of socioeconomic status.

Paints and pigments, especially in children’s toys and household paints are another major source of lead. Despite a regulation in place limiting lead content in paints, enforcement remains lax, allowing substandard products to circulate freely on the market. The consequences are particularly tragic for children, whose developing nervous systems are especially vulnerable to the neurotoxic effects of lead.

Lifelong burden for future generations

HEALTH implications of lead poisoning are staggering, particularly for children. Research has showed that there is no safe level of lead exposure; even a small amount can have lifelong impact on health and development. In children, exposure to lead is associated with an irreversible loss of intelligence quotient, attention deficit and behavioural disorders. The World Bank estimates that children in Bangladesh have lost more than 20 million IQ points collectively to lead poisoning. This impairment is not only a personal tragedy for those affected but a national setback as a generation of children grow up less able to contribute to work force and the economy.

Moreover, lead exposure affects more than just the brain. In adults, a chronic lead exposure contributes to hypertension, cardiovascular diseases and renal impairment. The cardiovascular toll alone is shocking, with lead exposure linked to an estimated 140,000 cardiovascular-related deaths among adults in Bangladesh annually. This burden falls disproportionately on the economically disadvantaged, who are more likely to live near informal recycling facilities or to work in high-risk industries. These are people who often have limited access to health care, meaning that the full extent of their lead exposure goes unaddressed until severe health complications arise.

Women and children are especially vulnerable. Lead exposure during pregnancy can cross the placental barrier, causing foetal lead poisoning, which results in low birth weight, pre-term births and developmental delays. Women exposed to lead face an increased risk of infertility and pregnancy complications. And for children under five, whose bodies absorb lead more readily than the adult, exposure leads to lifelong cognitive deficits, lower educational outcomes and an increased likelihood of involvement in the informal economy themselves.

Economic and social costs of inaction

LEAD poisoning is an economic drain on a nation’s resources and potential. The cognitive deficits among children lead to lower educational achievements, reducing productivity and earnings potential in adulthood. The World Bank report emphasises that the annual economic loss from lead-induced cognitive impairment alone is $10.9 billion or 3.6 per cent of the country’s gross domestic product. If cardiovascular costs and premature mortality are also considered, the total economic cost rises to an unsustainable $28.6 billion.

The financial strain on the healthcare system is profound. Lead exposure exacerbates already high healthcare costs, forcing limited resources to be directed towards treating preventable conditions. With healthcare access already limited for many in Bangladesh, lead poisoning puts additional pressure on an overstretched system. The economic and healthcare consequences of lead poisoning are intricately linked, creating a cycle of poverty and illness that is difficult to break. Addressing this issue could not only save lives but also redirect valuable resources to more pressing developmental goals.

From policy to enforcement

TACKLING the lead crisis requires a coordinated, multi-sectoral response that prioritises both preventative and remedial actions. The World Bank’s 10-point action plan offers a blueprint for a sustainable solution. However, merely having a plan is insufficient. The recommendations of international organisations must be implemented on the ground with stringent enforcement.

First, we must strictly regulate and enforce laws. Bangladesh already has laws prohibiting high lead levels in paint and consumer products, but the laws are seldom enforced. A lack of enforcement creates a permissive environment for informal and unsafe practices, especially in battery recycling. Adopting a ‘polluter pays’ principle could hold industries accountable and incentivise safe practices.

Monitoring and screening programmes are essential. Routine blood lead level test, particularly in children, should become a part of standard healthcare protocols. This could provide data necessary for the identification of high-risk areas and segments of the population, enabling targeted interventions. Awareness campaigns, both at the community and national levels, are equally important. Educating the public in the dangers of lead poisoning and safe disposal and recycling practices can empower communities to protect themselves and demand change.

Second, we must provide resources to remediate contaminated sites, particularly in densely populated areas. Informal battery recycling facilities, once identified, should either be formalised and regulated or relocated to industrial zones where exposure can be better managed. The government should incentivise formal recycling facilities that adhere to international safety standards and phase out informal recycling practices.

Finally, public-private partnership schemes could play a crucial role in addressing lead exposure from consumer products. By collaborating with businesses, we can ensure safe production practices and improve the quality control of imported goods, particularly in sectors such as spices, toys and cosmetics. Engaging civil society and international partners can further bolster the efforts, ensuring that Bangladesh is not alone in tackling this crisis.

A national imperative

LEAD poisoning in Bangladesh is a public health crisis that demands urgent action. The costs — human, economic and developmental — are too high to ignore. Failures to act now condemn another generation to unnecessary suffering, robbing children of their potential and costing the nation invaluable human capital. Tackling lead poisoning is not only a moral obligation but a national imperative.

The government, civil society and international partners must work together to make Bangladesh a model of effective lead prevention. The task is monumental, but with determination, collaboration and effective policy implementation, we can mitigate effects of lead poisoning, protect future generations and secure a healthy, prosperous future for all.

Dr Rakib Al Hasan is a physician, writer, activist and international award-winning youth leader of Bangladesh. He is founder and executive director of the Centre for Partnership Initiative.

https://www.newagebd.net/post/opinion/248812/steep-price-that-children-pay

Comments