You'll never guess the culprit in a global lead poisoning mystery. “They found the cheapest yellow pigment available at that time,” Forsyth says. The vibrant yellow pigment was lead chromate. It’s often used in industrial paints – think of the yellow of construction vehicles.

September 23, 2024 5:15 PM ET

Heard on All Things Considered

“It’s the crime of the century,” says Bruce Lanphear.

He’s not talking about a murder spree, a kidnapping or a bank heist.

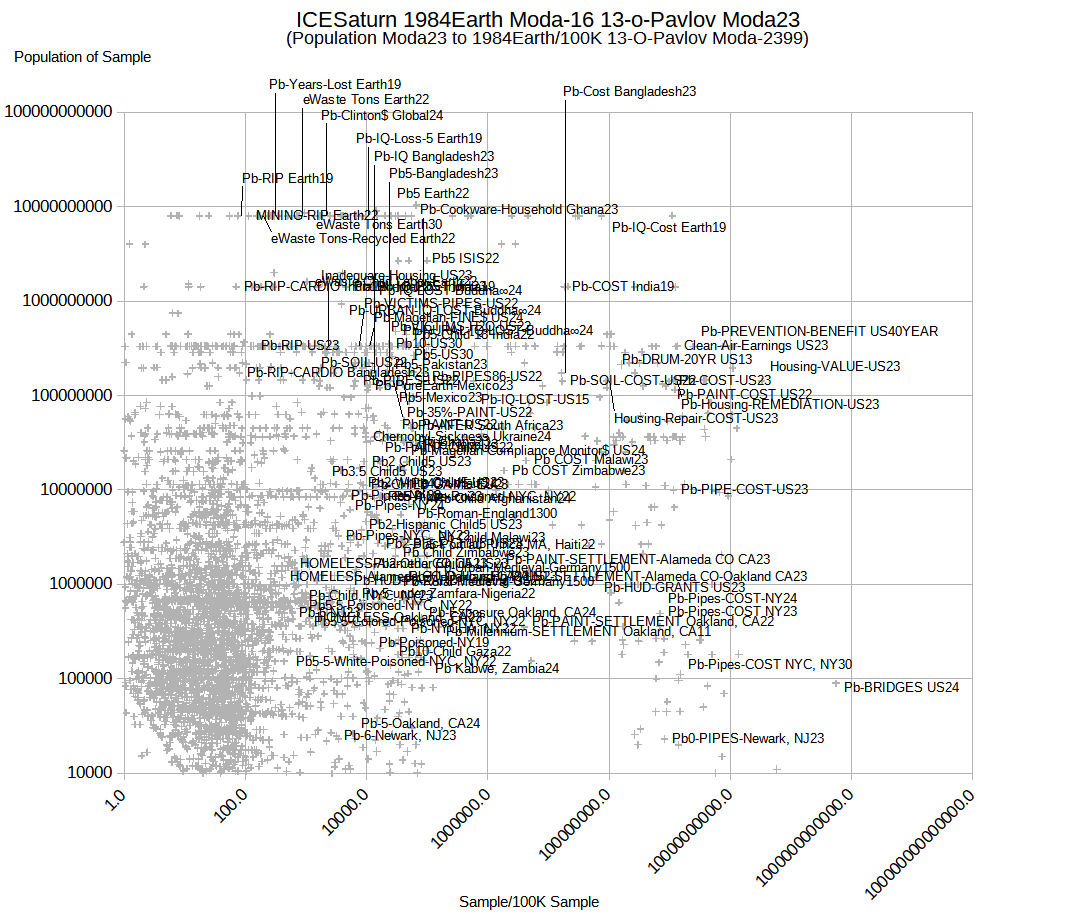

Lanphear – an environmental epidemiologist at Simon Fraser University – is referring to the fact that an estimated 800 million children around the world are poisoned by lead – lead in their family’s pots and pan, lead in their food, lead in the air. That’s just about half of all children in low- and middle-income countries, according to UNICEF and the nonprofit Pure Earth.

For decades, very little has been done about this. But this is the story of how two women – a New York City detective and a California student – followed the data and helped crack a puzzling case that spanned the globe in the ongoing “crime” of lead poisoning.

Meet New York’s lead lead detective

Next to a row of courthouses in downtown Manhattan, there’s an imposing gray building. On the 6th floor is an office that houses about 50 detectives. They work for New York City’s health department. They tackle thousands of cases a year involving kids exposed to toxic elements. And many of those cases are children who have too much lead in their blood.

The detectives’ job is to find the culprit. Could it be old chipping paint that’s creating lead dust that kids are breathing in? Could the lead be coming home on a parent’s clothes from, say, a factory or construction worksite and, then, the child breathes it in? Perhaps it was a toy from overseas, decorated with lead paint, that the kid repeatedly puts in their mouth?

The city detectives often search the child’s home armed with a device that resembles a radar gun – point it at, say, a wall, hold the trigger and you get a lead measurement of its paint.

Every time you go on such a mission, “it is absolutely a lead detective mystery,” says Paromita Hore, who oversees the detectives as director of environmental exposure assessment and education in the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene.

When the mystery is solved — when they find the source of the lead — Hore’s team helps the family avoid additional exposure.

In the early 2000s, New York City's health department noticed a perplexing blip: A surprisingly large number of Bangladeshi children in New York City were showing up in their lead database.

“This is a problem,” Hore recalls thinking throughout the multi-year, multi-country effort to unearth the root cause.

Another mystery involving Bangladesh

As Hore’s team of lead detectives busily collected and analyzed samples from items found in the homes of New York’s Bangladeshi families, a student in California stumbled on a similar mystery.

Jenna Forsyth was a Ph.D. student in 2014 when her adviser gave her data on over 400 pregnant women in rural Bangladesh. He’d noticed that about half of the women had high levels of lead in their blood.

“I was kind of like, ‘Lead? I don't know. Is that really still that big of a problem?” she remembers thinking to herself. “‘We don't hear about it much anymore.’”

Then, she started reading the literature. And she quickly understood the severity of the Bangladesh lead levels. Lead can damage nearly every organ — from the kidneys to the heart — often irreversibly. In this case, both the woman and the fetus would be affected.

Perhaps lead’s biggest impact is on the brain. Exposure can lower a child’s IQ and spur cognitive decline in adults. It can cause long-term problems with impulsivity, attention and hyperactivity. When you look at the gap between what kids in upper-income and lower-income countries achieve academically, about 20% can be attributed to lead. Treatment can involve vitamin supplements or prescribing an agent that binds to the lead and helps remove it.

Lead exposure is also linked to cardiovascular disease, kidney damage and fertility problems, to name a few. It’s estimated that lead kills 1.5 million people each year in addition to those marked by disability and disease. Plus, a series of studies have linked increased lead exposure to societal ills, like higher crime rates and more violence — likely because lead has been linked to reduced brain volume and impaired brain function.

The World Bank took a stab at estimating how much this all costs – including the lost IQ points, the premature death and the welfare costs. They found the world's price tag for lead exposure is a whopping 6 trillion dollars annually – nearly 7% of the global gross domestic product.

.../...

Two cases solved, millions to go.

Today, Jenna Forsyth runs a global lead initiative at Stanford School of Medicine. She still teams up with icddr,b and, she says, they’re really busy.

“In Bangladesh, the case is closed on turmeric,” says Forsyth. “But when my friend was like, ‘You should take a break.’ I said, ‘No way. There’s more to be done.’ ”

Forsyth has found lead in spices in other countries, including parts of India and Pakistan. And in Dhaka, despite the lead-free turmeric, 98% of the kids she’s tested have lead poisoning by the U.S. CDC standard. “It’s wild,” she says.

“It's enough to destroy a nation,” says icddr,b’s Rahman.

She and icddr,b are in the process of teasing apart all the possible culprits that still lurk in Dhaka and in so much of the world: lead acid batteries that are improperly recycled; pots and pans made with scrap metal that contains lead; cookware glazes where it’s not fired to a high enough temperature and lead can leach into food; cosmetics – like the eye make-up surma and sindoor, the traditional powder used in Hindu practices – have been found to contain lead.

Paromita Hore’s team of lead detectives are hot on the case too. They’re gathering data about cosmetics, among other things. She meets with Forsyth – and other lead experts – monthly to compare notes and piece together the next mystery.

And recently they are celebrating some big news on the lead fighting front: This week, UNICEF and the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) announced a new $150 million initiative to combat lead poisoning.

“There's been so little done for so long, that this is really huge,” says Lanphear of Simon Fraser University.

The money – most of it from Open Philanthropy – will go to more than a dozen countries from Indonesia and Uganda to Ghana and Peru. And there will be a new public-private partnership aimed at boosting government buy-in, international coordination and jump starting an effort to get lead out of consumer products.

“It is long overdue that the world is coming together,” says Samatha Power, who runs USAID.

“There is a broad perception that it requires billions of dollars to transform a national or municipal infrastructure … to address lead poisoning. But in fact, there is an awful lot of low hanging fruit,” she says. “There is lead right now in paint, in spices, in cosmetics in developing countries. We think within just a few short years we can make sure that that lead has been eliminated and that kids are safe to play with their toys, to go to their schools.”

But Forsyth isn’t ready to retire. She keeps looking for lead in the usual (and unusual) places. She’s motivated, she says, because “it’s just really hard to tell a parent their kid has lead poisoning.” One day, she dreams that she’ll never again have to deliver such devastating news.

Comments