Mayor Justin Bibb signed a surprise executive order in October shaking up the city’s lead paint program.

by Nick Castele December 12, 2024

After making an abrupt change in Cleveland’s approach to eradicating lead paint from homes, city officials are wading through a nearly 60-day backlog in landlords’ applications for lead-safe certificates.

A law passed in 2019 required landlords to prove their homes didn’t have high levels of lead dust. The recent change by Mayor Justin Bibb’s administration means they now need a more in-depth and expensive inspection for lead paint hazards.

Bibb administration officials could not say how many of the inspections had been submitted to the city since the mayor’s October executive order. That’s because the applications came via email in multiple file formats, and staff must reenter the data in a different city system, officials said.

That uncertainty led the chair of the city’s Lead-Safe Advisory Board to suggest City Hall was “fundamentally unprepared” to make the changes laid out in Bibb’s order. The order raised the standards that landlords must meet to obtain a city certificate saying that their properties are safe from lead paint and can be rented to tenants.

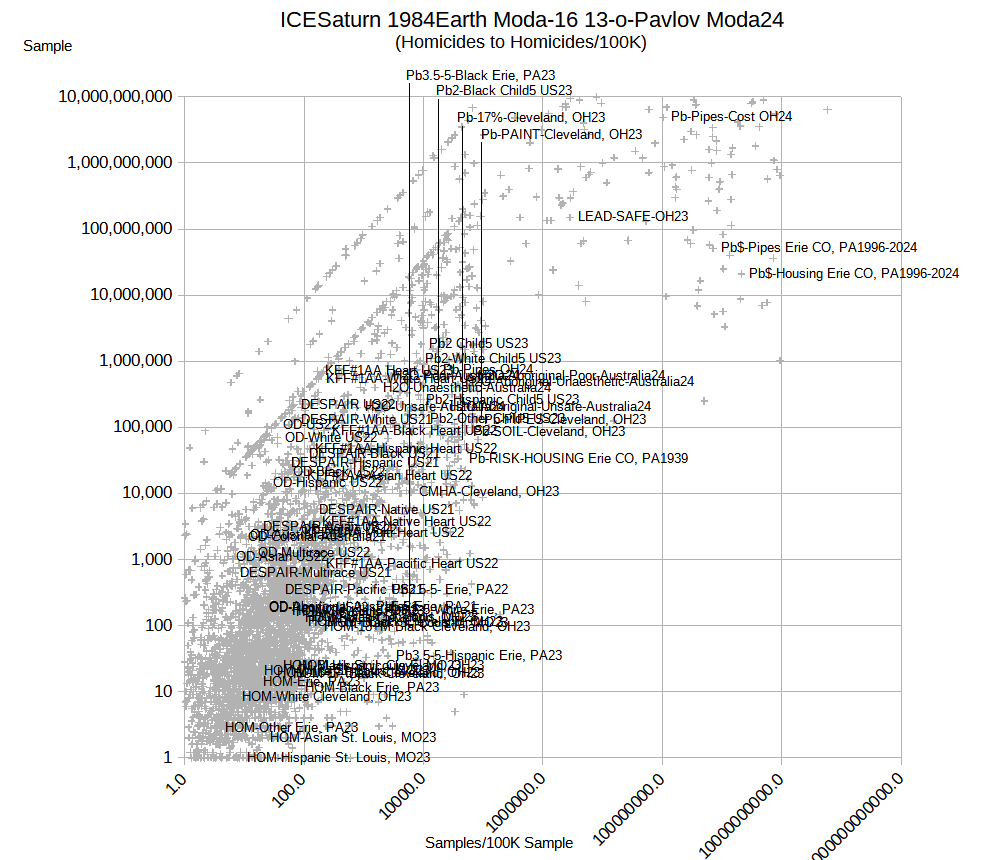

Meanwhile, city officials said stagnant childhood lead poisoning rates showed that urgent changes were necessary. The city’s data analytics office plans to set up a new portal for lead-safe applications in January.

“I am fundamentally disappointed that we got to the point where we forced through an executive order on four days’ notice that was a surprise to the workforce, that was not previewed publicly,” said Ward 12 Council Member Rebecca Maurer, who chairs the board, which was created to track the city’s progress toward a goal of having no children poisoned by 2028.

Non-profits and community partners who have for years worked with the city on a strategy to make more homes safe for children were also caught off guard by the move.

Maurer drafted a letter saying the city should have done more to prepare for its sudden pivot in lead paint strategy. At a meeting Thursday, the board opted to postpone a decision endorsing the letter.

City staff were “a little bit inundated” with lead-safe applications after the executive order, according to Liz Crowe, the director of Cleveland’s Office of Urban Analytics and Innovation. Now the backlog is “barreling towards 60 days,” she said.

“That was not great, I want to acknowledge that,” Crowe said at Thursday’s meeting. “But the executive order has really lit a fire under both the staff and the administration in terms of how we want to address this.”

City Hall is also awaiting the results of a yet-to-begin audit of its lead paint program, which is at least six months away. The city parted ways with its old auditor, Case Western Reserve University, and has hired the accounting firm Crowe LLP. The firm also advised the city on its revamp of the Department of Community Development.

Debate over quantity versus quality

Cleveland overhauled its approach to lead poisoning in 2019, but the work has been slow. The previous auditor, CWRU Professor Rob Fischer, warned earlier this year that the city was not certifying enough rentals as safe from lead paint.

In October, Bibb moved to raise the bar for inspecting rentals for lead paint. He pointed to 11 instances in which children who lived in lead-safe-certified properties had nonetheless been poisoned.

The change hinges on a push-and-pull between quantity and quality. Critics of Bibb’s move have questioned how City Hall can require more in-depth lead inspections when it was lagging behind under the old standard.

“We just have to be realistic about how a more burdensome process, a more involved hands-on process from the city is going to slow things down,” Fischer said.

Cleveland Health Director Dr. David Margolius argued on Thursday that the number of certificates wasn’t the most meaningful data to track if children in the city were still being poisoned by lead.

“We were counting this many lead safe certificates … while hearing anecdotally from realtors and landlords that they were cheating the system,” he said.

Cleveland has struggled to get landlords to prove homes are lead safe

Fischer disagreed, saying that the 11 poisoning cases and current poisoning rates weren’t enough evidence to say that the city’s approach had failed. So far, neither the city nor its coalition of nonprofit partners has been able to deliver the volume of certificates that everyone discussed, he said.

One unsolved conundrum facing Cleveland is how to persuade landlords to make their properties lead-safe if they could just avoid the city’s scrutiny in the first place. The city has the option to ticket landlords or take them to court if they don’t follow the rules, but that process also can be slow.

Zak Burkons, a lead inspector who attended Thursday’s meeting, gave the example of landlords who ask why they should renew their lead-safe certificates at all.

“They say, ‘Nothing personal, but the guy down the street hasn’t done it once. Why should I do it twice?’” he said.

Lead Poisoning

‘We continue to dive towards failure’: Cleveland lead safe efforts still short of goals

by Dakotah Kennedy and Cleveland DocumentersJune 21, 2024

Comments