M Jermane Bond 1,✉, Allen A Herman 1

Black men’s health disparities must be viewed within the larger context of public health, community wellness, and family formation. Healthy People 2020 recognizes both ecological and individual factors that determine health and wellness across the life span. Life expectancy summarizes the impact of risk across the life course.

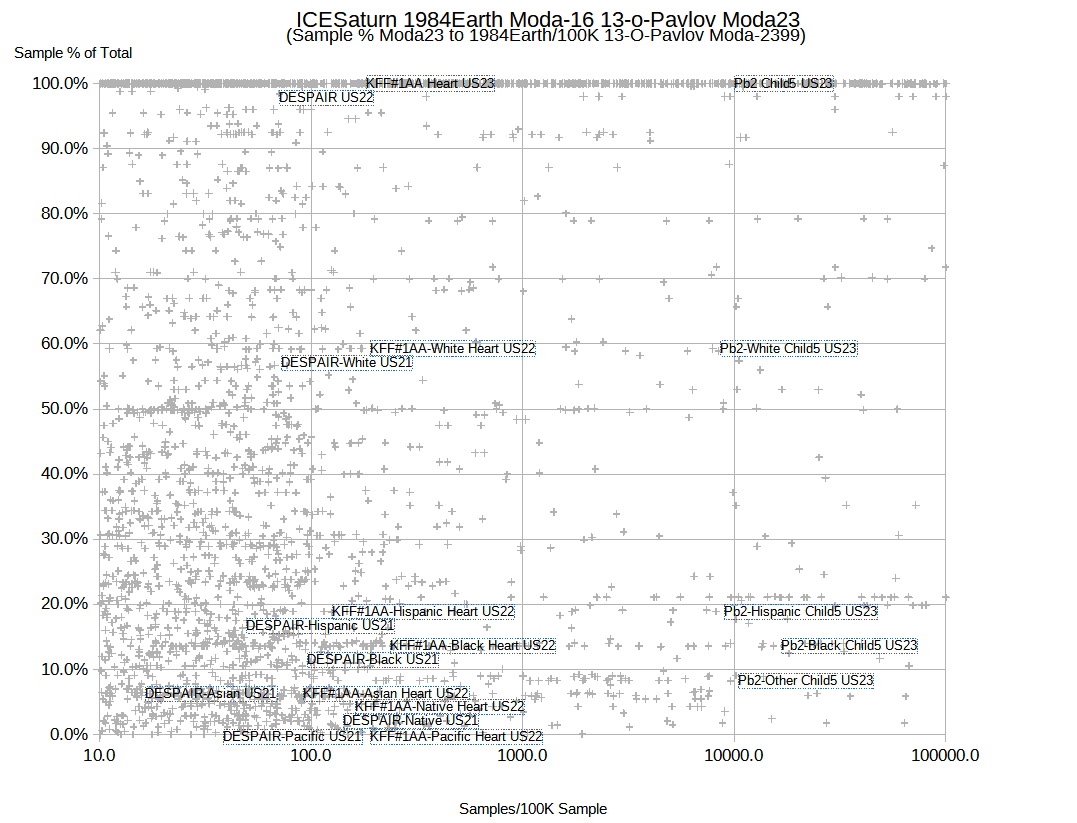

Consider life expectancy by race (Black:White inequities) and gender from 1900 to 2011. Although it has improved for all race/ethnicity and gender groups for the past 111 years, Black men continue to have substantially lower life expectancy at birth than Black women and White women and men (Figure 1a).1 In 1900, the estimated life expectancy for White men was 46.6 years; for non-White men it was 43.5 years; for White women it was 48.7 years, and for non-White women it was 33.5 years. By 2011, the life expectancy for White men was 76.6 years; for Black men it was 72.2 years; for White women it was 81.1 years; and for Black women it was 78.2 years. For both genders, the relative difference in life expectancy declined from a high of 34% in 1900 to a low of 4% in 2011 (Figure 1b). Relative differences in life expectancy declined at a steady rate until 1960, then plateauing for males and females until 1990. The plateau in relative ratios for men probably reflects an increase in mortality from homicide and HIV for young to middle-aged Black men. After 1990, the relative differences declined steadily for both men and women, reflecting annual increases in life expectancy (Figure 1b).

FIGURE 1—

United States Life Expectancy (a) at Birth (in Years) by Race and Gender and (b) Relative Difference (%) Overall and by Gender: 1900–2011

Source. National Center for Health Statistics of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and, for 1900–1928, states that were included in the vital records registration system of the United States (12 states by 1900 and 46 states by 1928).

Post-1990 improvements in expectation of life at birth primarily reflect increases in survival after age 75 years. These improvements have been larger for females than for males, and for Whites compared with Blacks. There is a lag in increases in survival between the ages of 45 and 75 years for Blacks with the largest gap in survival for Black men. Increases in maximum life spans have been comparatively small. Life table survival analysis shows that improvements in life expectancy in young through middle age are close to their limits (with survival rates > 90%). An examination of relative ratios in age-specific mortality rates for males reflects these race-specific changes. In 1960, relative ratios in age-specific mortality increased from birth to age 40 years (with Black male mortality rates from 40% to 230% higher than White male mortality rates) then declined to −10% at age 85 years (Black mortality rates were 10% lower at 85 years). In 2013, relative ratios remained relatively constant from birth to age 70 years (with Black male mortality rates about 40% higher than White male mortality rates) and then declined to 0% at age 85 years. Most of the improvement in life expectancy in the first half of the 20th century was attributable to the reduction in both infant and childhood mortality and reductions in deaths from acute infectious diseases. Rates of decline were slower for Black men and women, resulting in larger relative ratios in life expectancy.

Life expectancy and other health outcomes are affected by exposures to a wide range of social, economic, and biological risk factors during critical periods of the life course. Early life exposures increase disease risk and have cumulative lifelong negative effects on the structure and function of organs, tissues, and body systems.2 Some have labeled prenatal adverse exposures associated with poor growth in utero, low birth weight, or premature birth as “later life effect modifiers,” and have linked them to coronary heart disease, hypertension, and insulin resistance. Many historical, social, economic, physical, and biological risk factors shape the life course of Black men and contribute to their increased rates of premature morbidity and mortality. These include the role of the places and spaces where Black men and their families live, work, worship, and play; the risk that accompanies family formation in the Black community; and the increased individual social, economic, and behavioral risk that is associated with being Black in America.3–6

Comments