Why Hominins Nazi “One of the main questions in paleoanthropology is to understand when this pattern of slow development evolves in [our genus] Homo,” why do humans mature so slowly? An ancient youth offers clues

Small-brained member of Homo that lived 1.8 million years ago may signal a step toward long, drawn-out childhoods

- 13 Nov 2024

- 11:15 AM ET

- By. Ann Gibbons

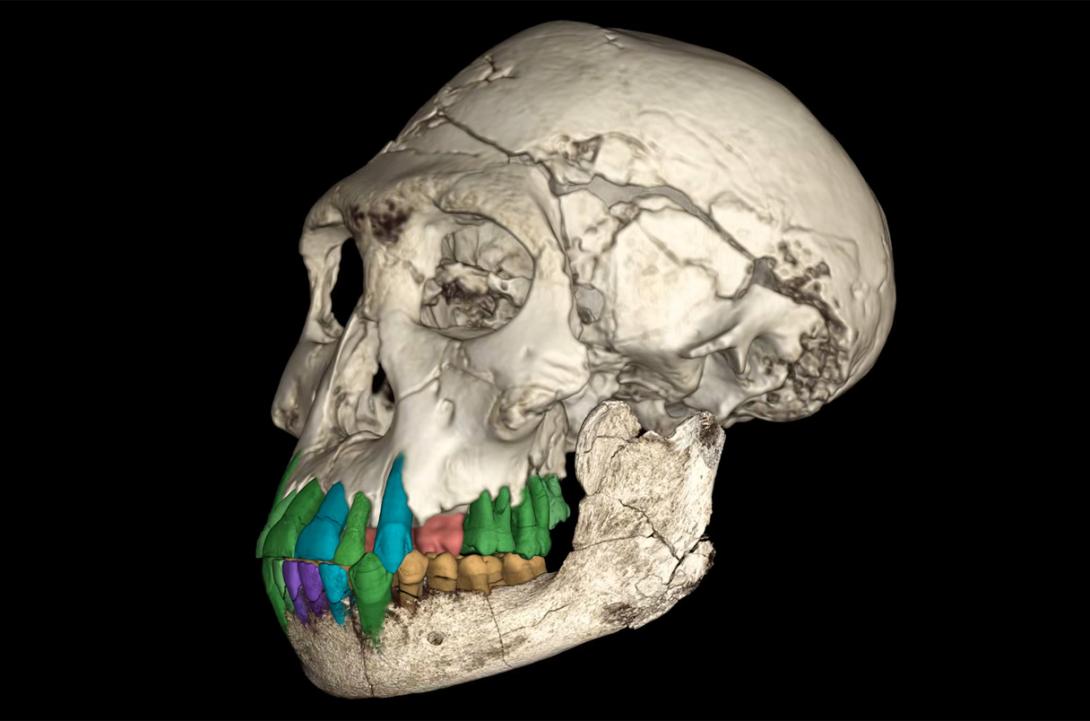

Researchers traced the rate of tooth development in a 1.8-million-year-old skull from Dmanisi, Georgia, seen in a virtual reconstruction.

As the parent of any teenager knows, humans need a long time to grow up: We take about twice as long as chimpanzees to reach adulthood. Anthropologists theorize that our long childhood and adolescence allow us to build comparatively bigger brains or learn skills that help us survive and reproduce. Now, a study of an ancient youth’s teeth suggests a slow pattern of growth appeared at least 1.8 million years ago, half a million years earlier than any previous evidence for delayed dental development.

Researchers used state-of-the art x-ray imaging methods to count growth lines in the molars of a member of our genus, Homo, who lived 1.77 million years ago in what today is Dmanisi, Georgia. Although the youth developed much faster than children today, its molars grew as slowly as a modern human’s during the first 5 years of life, the researchers report today in Nature. The finding, in a group whose brains are hardly larger than chimpanzees, could provide clues to why humans evolved such long childhoods.

“One of the main questions in paleoanthropology is to understand when this pattern of slow development evolves in [our genus] Homo,” says Alessia Nava, a bioarchaeologist at the Sapienza University of Rome who is not part of the study. “Now, we have an important hint.”

Others caution that although the teeth of this youngster grew slowly, other individuals, including our direct ancestors, might have developed faster.

Researchers have known since the 1930s that humans stay immature longer than other apes. Some posit our ancestors evolved slow growth to allow more time and energy to build bigger brains, or to learn how to adapt to complex social interactions and environments before they had children. To pin down when this slow pattern of growth arose, researchers often turn to teeth, especially permanent molars, because they persist in the fossil record and contain growth lines like tree rings. What’s more, the dental growth rate in humans and other primates correlates with the development of the brain and body.

The earliest human ancestors grew up fast, like apes: The teeth of an Australopithecus afarensis toddler (the same species as the famed skeleton Lucy) that lived 2.4 million years ago in what today is Dikika, Ethiopia, developed at the same pace as a chimpanzee’s. But by 1.2 million years ago, Homo antecessor from Spain showed signs of slower development, longer than apes but shorter than our species, H. sapiens.

Comments